Whatever you write: blog posts, short stories, client pieces – I suspect that, at some point, you’ve at least considered writing a novel.

Maybe it’s something you contemplate every November, when NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) rolls around. Or maybe you’ve had an idea bubbling away for years now, but you’ve been waiting until you have more time to write.

His response

Writing a whole novel might feel rather daunting, especially if you’ve only ever written shorter pieces before. You may well wonder where to even begin.

Whether you’ve always wanted to write a novel, ever since you started reading “chapter books” as a child … or whether it’s a more recent ambition, this post will take you step by step through what you need to do.

Step #1: Choose Your Genre

In fiction, “genre” describes different types of novel. For instance, “science fiction” is one genre and “romance” is another. Within big genres like that, there are also subgenres (e.g. compare “dystopian fiction” with “space opera”, or “steamy romance” with “Amish romance”).

Some authors know exactly what genre they want to write in: they enjoy reading, say, psychological thrillers and they want to write something similar.

Other authors aren’t sure. Perhaps they have an idea for a novel that doesn’t really fit an established genre. If that’s you, think about where your book could potentially be shelved in a bookstore. What other books are similar? What books are definitely not like it?

It’s important to pin genre down before going much further because most genres have quite specific requirements. Romance readers tend to expect short novels, for instance … and a happily ever after ending.

Step #2: Settle on an Idea

You might have a bunch of different ideas for novels, or maybe just one idea that you’ve been carrying around for a long time. Novels have all sorts of starting points – C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe stemmed from an image that Lewis had in his head of “a Faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood.”

If you don’t currently have an idea that you’re interested in writing about, don’t force yourself to come up with something. A novel is a big commitment of time and energy – you don’t want to embark on it if you’re not feeling engaged with your idea from the very start.

Do, however, be open to ideas. They might come from anything – a hobby, a news story, a very different novel, a piece of art or music, a friend’s dilemma. Wait until your idea arrives.

If you have an idea that you’re unsure about – maybe it has mileage, maybe it doesn’t – then try writing it as a short story or a novel excerpt. See if it falls flat, or if you find that you want to continue working on it.

Step #3: Develop Your Characters and the Relationships Between Them

What’s more important, plot or character? It’s a trick question, really: you can’t separate the two. The plot of a story is driven by the characters’ actions; the characters’ growth (or “character arc”) is driven by the plot.

Personally, I find it easiest to develop characters first, then think about the ins and outs of the plot. If you’re working in a plot-focused genre (like action adventure) then you might prefer to start with the plot and then develop characters to fit it.

When you’re thinking about characters, you’ll want to work out a core cast for your novel. Don’t be tempted to throw in everyone – regardless of how “realistic” it might be. Yes, your characters probably have parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, best friends … but you don’t need to include all those unless they actually have a place in your story.

One technique for working out your characters is to get a piece of blank paper and draw a mindmap. Put each character’s name in a circle and work out how they relate to the other characters. Think about their key characteristics. (Are they cripplingly shy? Dangerously hubristic?) This is a good point to start working out which characters might come into conflict.

Your story may not have a “villain” as such, but it’s likely that there’ll be some major characters who play an antagonistic role. They could be well-meaning (e.g. a bumbling office-mate), a bit unpleasant (e.g. a glamorous and witheringly sarcastic mother-in-law) or downright nasty (e.g. a neighbour with serious anger-management issues).

Step #4: Decide How You’re Going to Tell Your Story

With novels, you’ve got some crucial choices to make about how you tell the story. You need to decide on whether you’ll write it in the first person (“I”) or the third person (“he/she”), and also whether you’ll use past or present tense.

(Technically, using the second person, “you”, is also an option, but I’ve never seen a novelist pull that off! It can work for a short story.)

There’s no “right” answer about whether to choose first or third person. With first person, present tense is fairly common (“I roll over in bed and reach for the alarm clock…”) but plenty of first person novels are written in past tense (“I rolled over in bed and reached for the alarm clock…”).

Third person present tense is seen as a slightly more unusual, literary choice (“He rolls over in bed and reaches for the alarm clock…”) but if it’s a good fit for your novel, go for it.

You’ll also want to think about how many viewpoints (also called perspectives) you want to use. With first person novels, it’s fairly normal to stick to a single viewpoint, but that’s not a hard and fast rule. With third person novels, it’s common to have more than one viewpoint, but to stick with one character’s perspective for each scene, only showing their thoughts and feelings.

If you’re not sure how best to tell the story, take a look at what other novels in your genre do.

Step #5: Think About Potential Sources of Conflict

Stories are driven by conflict – with no conflict, there wouldn’t be much story! Conflict comes in different flavours. Here are some key ones:

Internal – this is when a character’s struggles come from their own mind. For instance, they might be very anxious or shy, or they might find it very hard to connect to other people due to trauma in their past.

Interpersonal – this is conflict between characters. For instance, your character might get into a parking dispute with someone else in their block of flats.

Environmental – this is conflict that arises from an aspect of the character’s environment: for instance, it could be a physical limitation that they have, a financial problem, or a snowstorm that prevents them from getting to work.

Obviously, the different types of conflict can overlap – a financial problem might lead to interpersonal conflict (e.g. one spouse hiding difficulties from another) and to internal conflict (e.g. if the character needs to steal in order to feed their kids).

Look at your main character(s) and figure out what conflict you could throw in their path. Who might they end up arguing (or even fighting) with? What internal struggles are they trying to overcome? Is there anything in their environment that could make their life harder?

Step #6: Work Out a Rough Plot

Some authors write highly detailed outlines in advance … I’m not one of them! I do think it’s important to have a rough plot in mind, though; otherwise, you risk writing pages and pages that simply go nowhere.

Here are some good questions to ask yourself at this stage:

Where does your story begin? What kicks off the action? How do things get worse for your protagonist? How does it all end?

You can be as detailed (or not!) with your plans as you like. Keep in mind that you may find you want to change things as you go along, especially if this is your first novel – so don’t spend so long on planning that you’ll resist making necessary changes.

Novelist K.M. Weiland has some great resources on story structure that you might want to check out when you’re plotting your novel.

Step #7: Write the First Draft of Your Novel

This is a pretty big step! You might be surprised that it comes so far down the list – but there’s no point starting your first draft without any idea about your characters and plot.

Some authors like to write their first draft by jumping around between different scenes: they write whatever inspires them on a particular day, then they piece it all together at the end. I don’t think that’s a great approach for most novelists – it can lead to you leaving all the hardest scenes till last, for instance (and running out of steam altogether), and it makes it really tricky to have a natural flow of action and of character development.

So I’d recommend tackling your novel from beginning to end, drafting each scene as best as you can – whilst remembering that it is a draft that you’ll later be able to edit. Don’t aim for perfection at this stage.

Finishing your first draft will almost certainly take several months, and quite possibly a year or more. It’s easy to lose momentum partway, especially if this is your first attempt at a novel. If you’re struggling to keep going, there are some tips at the end of this article that will hopefully help.

Step #8: Read Through Your Whole Draft

Once you’ve finished your first draft, give yourself a huge pat on the back! This is the point in a novel where I like to break out some sparkling wine and celebrate having reached “the end”.

Of course, there’s still more work to do, but take a few days off first – not just for your sake, but also to give yourself the chance to return to your novel with fresh eyes.

After a break, read through your whole draft novel. I like to do this on my Kindle (you can send a Word document to your Kindle by following Amazon’s instructions here) – but you might want to print out your manuscript or even get it bound into a book by a print-on-demand service like Lulu. However you choose to read your novel, I’d suggest avoiding reading it in the same software in which you wrote it – you want to try to see it from a reader’s, rather than a writer’s, perspective.

As you read through the draft, jot down notes about any major changes that you think you need: chapters you might delete, scenes you might add, characters who aren’t really working, and so on. Don’t worry too much about little details at this stage – a clunky sentence here, a wordy bit of dialogue there. These might well get changed or cut during your revisions anyway, and you’ll do a close edit at a later stage.

Step #9: Redraft Your Novel

Redrafting is sometimes called “revising” which means “re-seeing” – this is your opportunity to see your novel afresh and shape it accordingly. You may well find that you need to make major changes – like cutting out big chunks of your story, fixing plot holes, removing or adding characters, and so on.

I know how frustrating it can be to cut thousands of words that you spent hours and hours working on – but ultimately, if those words are making your novel weaker rather than stronger, they need to go. The words you cut out aren’t wasted: they were an important part of the writing process, and they helped you get to this point.

(It’s very normal for novelists, even highly experienced ones, to make major changes at this point. Novels are complex, messy things!)

As with drafting, I like to approach redrafting sequentially: I start on page one and work forward. This means that I can incorporate major changes (like the removal of a character) throughout as I tweak other things, and I can make sure that the pacing and flow of the story still works.

Step #10: Do a Close Edit of Your Novel

The final step is to do a line by line edit of your novel. By this stage, you should be happy with all the major building blocks of your novel: your characters, the scenes, the key points in your plot. During this step, you’re not making major changes, just little tweaks.

As you edit your novel, line by line, look out for things like:

- Awkward dialogue – maybe it sounds stilted, or it goes on too long.

- Clunky sentences (you might want to read aloud to listen for ones that sound off).

- Anything that doesn’t fit with your revisions – e.g. maybe you changed a character so they were much more decisive than before, but you have a couple of paragraphs where they’re dithering about a course of action.

- Mistakes and typos – obviously check anything that your spell-checker has flagged up, but don’t trust it to have necessarily spotted all the mistakes. (Conversely, don’t blindly obey the spell-checker – sometimes its suggestions are wrong!)

Whew! You should now have – after probably a year or more – a finished, polished novel. This is the stage at which you could start thinking about submitting it to literary agents, or looking into self-publishing it.

I wanted to finish, though, with some key tips that fit across several of the different steps – I hope these will help you stay on track and produce the best novel you can.

Five Key Tips for Writing a Novel

Tip #1: Set Aside Regular Time for Your Novel

Whichever step of the plan you’re working on, you need to put time aside for it. (Even planning takes time – sometimes a surprising amount of it.) You don’t need to work on your novel every day, but if you want to see steady progress, I’d suggest finding 3 – 4 hours per week for it. That might mean 30 minutes a day or 2 hours every Monday and Thursday evening.

Tip #2: Get Feedback and Support

Most towns will have a local writers’ group (or several) – ask around! If nothing exists, talk to your local library about starting something up. A supportive group of writers will be invaluable in so many ways: you’ll meet likeminded people who “get” writing, and you’ll be able to get feedback from them on your work in progress.

Tip #3: If You’re Self-Publishing, Hire an Editor

If you plan to self-publish your novel, I’d strongly recommend hiring a professional editor. This won’t come cheap (you’re probably looking at $1,000 or more to edit a whole novel manuscript) – but it’s an essential part of publishing something of a professional standard. If you can’t afford to get your whole novel edited, at least pay for an editor to read and review your first few chapters – any issues they spot with those might well be repeated elsewhere in your novel.

Tip #4: Each Scene Should Have a Point

Every scene — in fact, every sentence! — in your novel should have a point. Avoid scenes where characters sit around drinking coffee and chatting, or even scenes where they bicker – unless there’s an actual purpose to it. It’s worth asking yourself, as you edit, “Does this scene advance the plot?” (If a scene reveals character, that’s important too – but there’s not much point showing us more about a particular character unless something is happening as a result.)

Tip #5: Keep a Writing Journal or Record

Every time you finish a writing session, make a quick note of what you achieved (or not)! This could be as simple as logging your wordcount for the day – but you might want to go further and include notes on how you felt about it (e.g. how focused you were, how much you enjoyed writing that scene) as well as anything you want to remember later on in the novel (e.g. that you’ve established a character has a brother, for instance).

Writing a novel is a major undertaking, but one that I hope you’ll find very rewarding. I think it’s something that every writer should attempt at least once. Work through the steps above, and this time next year, you could have a finished draft … and perhaps even a complete, edited novel. Best of luck!

Get our premium subscription and start receiving our writing tips and exercises daily. It costs less than a coffee per month! Click here to activate your Pro subscription.

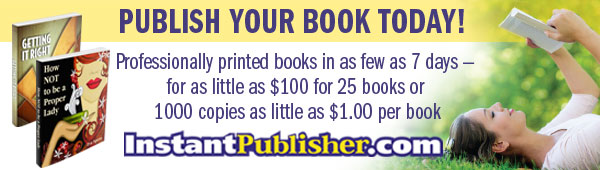

Publish your book with our partner

InstantPublisher.com! Professionally printed in as few as 7 days.

Original post:

How to Write a Novel: 10 Crucial Steps

from Daily Writing Tips

https://www.dailywritingtips.com/how-to-write-a-novel/